A brief history of the typewriter

The following is an exposition on the history of the typewriter and its relation to the QWERTY layout.

In the beginning

I was a few years into my career as a software engineer, and increasingly I was experiencing hand, finger, and wrist pain. The nature of the work, involving a substantial amount of typing each day, was becoming strenuous on my hands. Somewhat fear-stricken — given the essential role of typing in software engineering — I started researching in more depth the ergonomics of typing.

Aside from general postural improvements, my main approach was in experimenting with various so-called ergonomic keyboards. I soon learned about the myriad types of ergonomic keyboards — split keyboards, contoured keyboards, angled keyboards. While some of these options provided relief, my pain would inevitably eventually return.

At one point, I happened to stumble on an article regarding the history of the QWERTY keyboard layout. I was intrigued, to say the least. Until then I had not thought deeply about the history of the QWERTY keyboard layout. I, like most people, I imagine, had taken the QWERTY keyboard layout for granted. Out of curiosity, I decided to look deeper into the history.

A brief history of the typewriter

The history of typewriters is actually quite rich, and too much to cover exhaustively here. I will however give an overview in bullet-point form here (you will understand the connection with ergonomics in the next section).

work on the typewriter started in Wisconsin

specifically, Milwaukee, between 1867 and 1873

although others were involved to varying degrees, the two main people involved were C. Latham Sholes1 (inventor) and James Densmore2 (promoter)

- both had been publishers of Wisconsin newspapers

inspired by the July 6, 1867 issue of the Scientific American

makes mention of a type writing machine prototype by John Pratt3

side note, Alfred Ely Beach, an early owner and cofounder of Scientific American, was himself also an inventor of a writing machine

- worked in Kleinsteuber Machine Shop4

also worked with

idea to move away from one solid plate to separate hammers or type bars

James Densmore begins financing the project

- Densmore had former involvements in the oil business in Pennsylvania

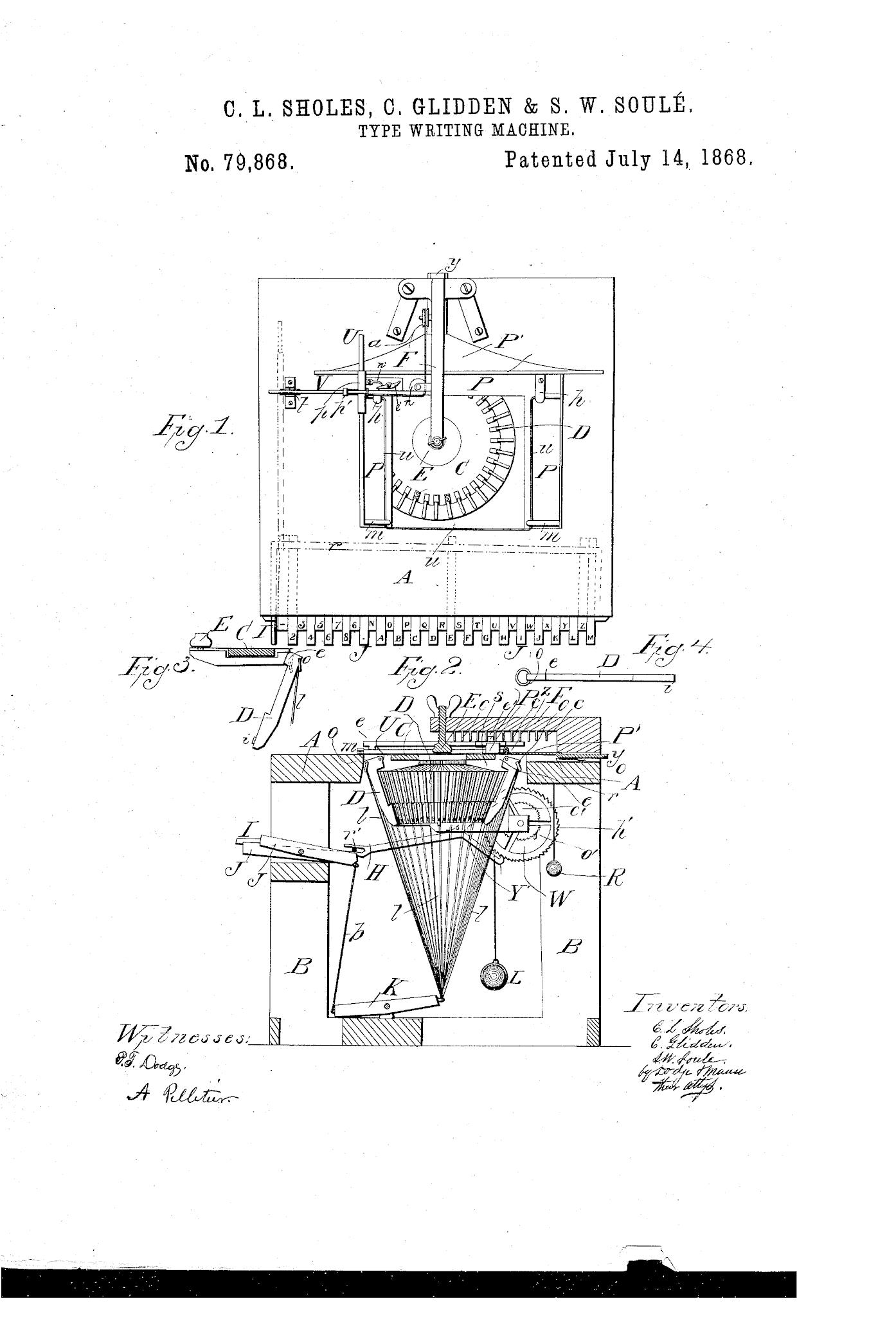

by 1868 there are two versions of the typewriter

secure a patent for both

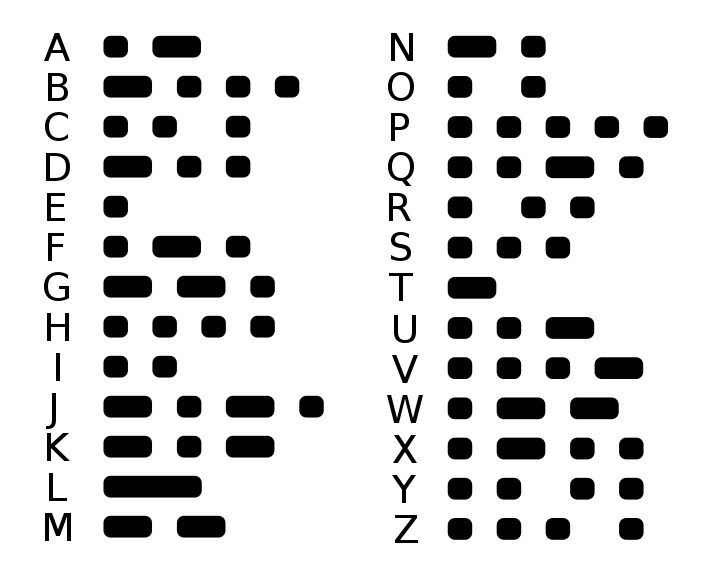

- an early physical prototype- described as a “literary piano” the keys were arranged in alphabetical order with the letters A through M on one row and the letters N through Z on the other

. - 3 5 7 9 N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

2 4 6 8 . A B C D E F G H I J K L M- note the resemblance between this and the earlier (1846) printing telegraph10 used for message transmission

manufacturing begins in small quantities

- E. Payson Porter11, head of a school for telegraphers in Chicago, begins using them

Densmore decides the unit is not ready, temporarily abandons manufacturing

Sholes begins working on modifications

Soulé and Glidden sell their rights to the original patent

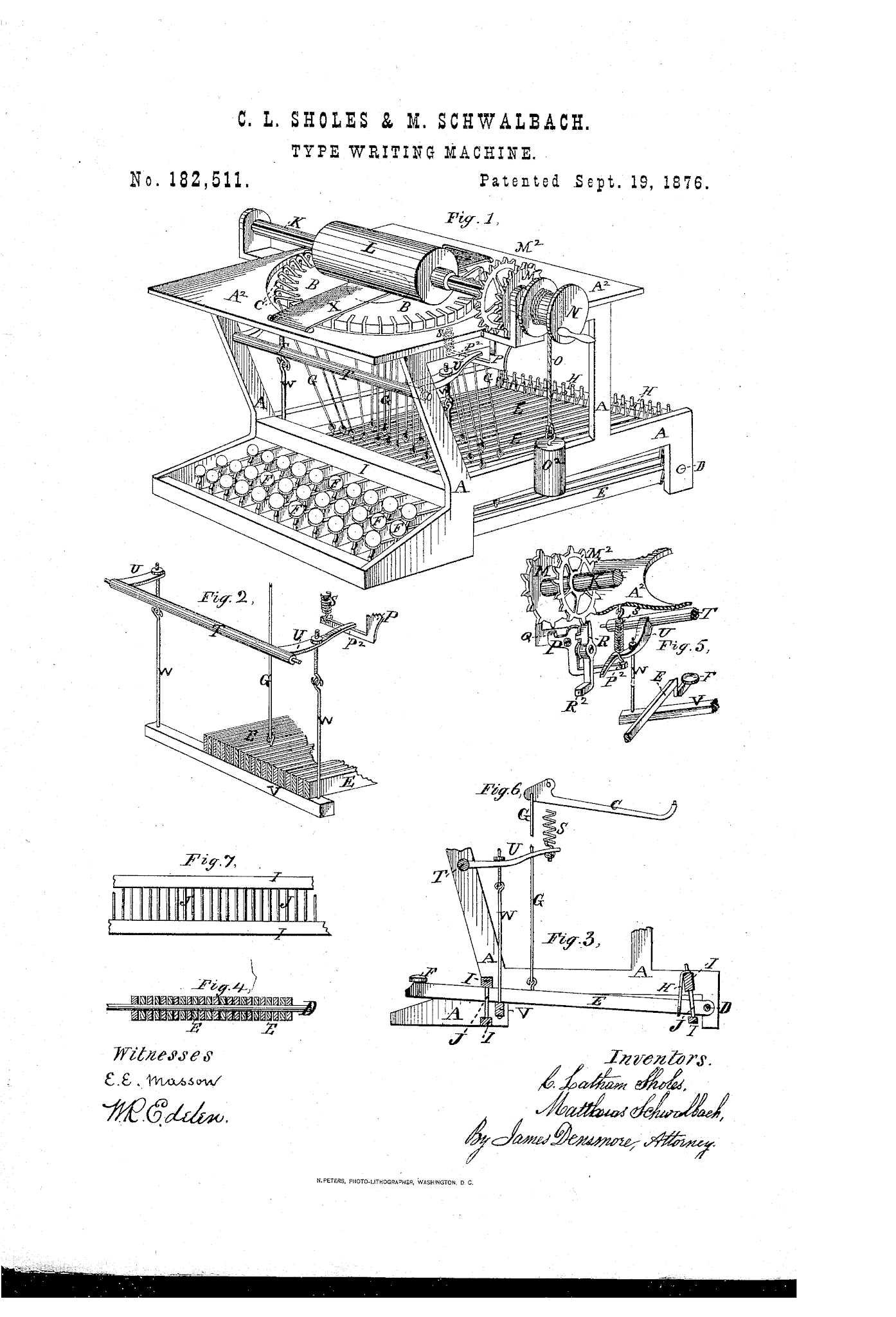

Sholes adopts a four-bank keyboard (the idea attributable to Schwalbach)12

Schwalback’s contribution to the multi-bank layout would be later more explicitly acknowledged in a joint patent13 with Sholes in September, 1876

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 -

A E I . ? Y U O ,

B C D F G H J K L M

Z X W V T S R Q P Nfour-bank layout

vowels (A, E, I, O, U, Y) positioned on the third bank from the bottom

second bank in alphabetical order

first bank in reverse alphabetical order

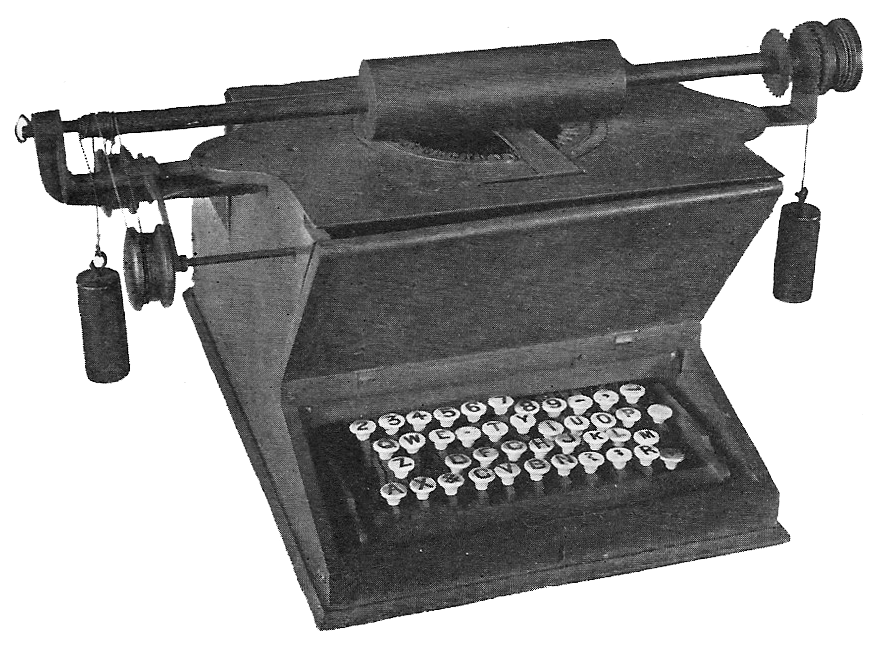

in February, 1873 the following model is presented to Remington

- note the modified layout

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 - ,

Q W E. T Y I U O P

Z D F G H J K L M

A X & C V B N ? ; RDensmore and Remington sign a contract for manufacturing

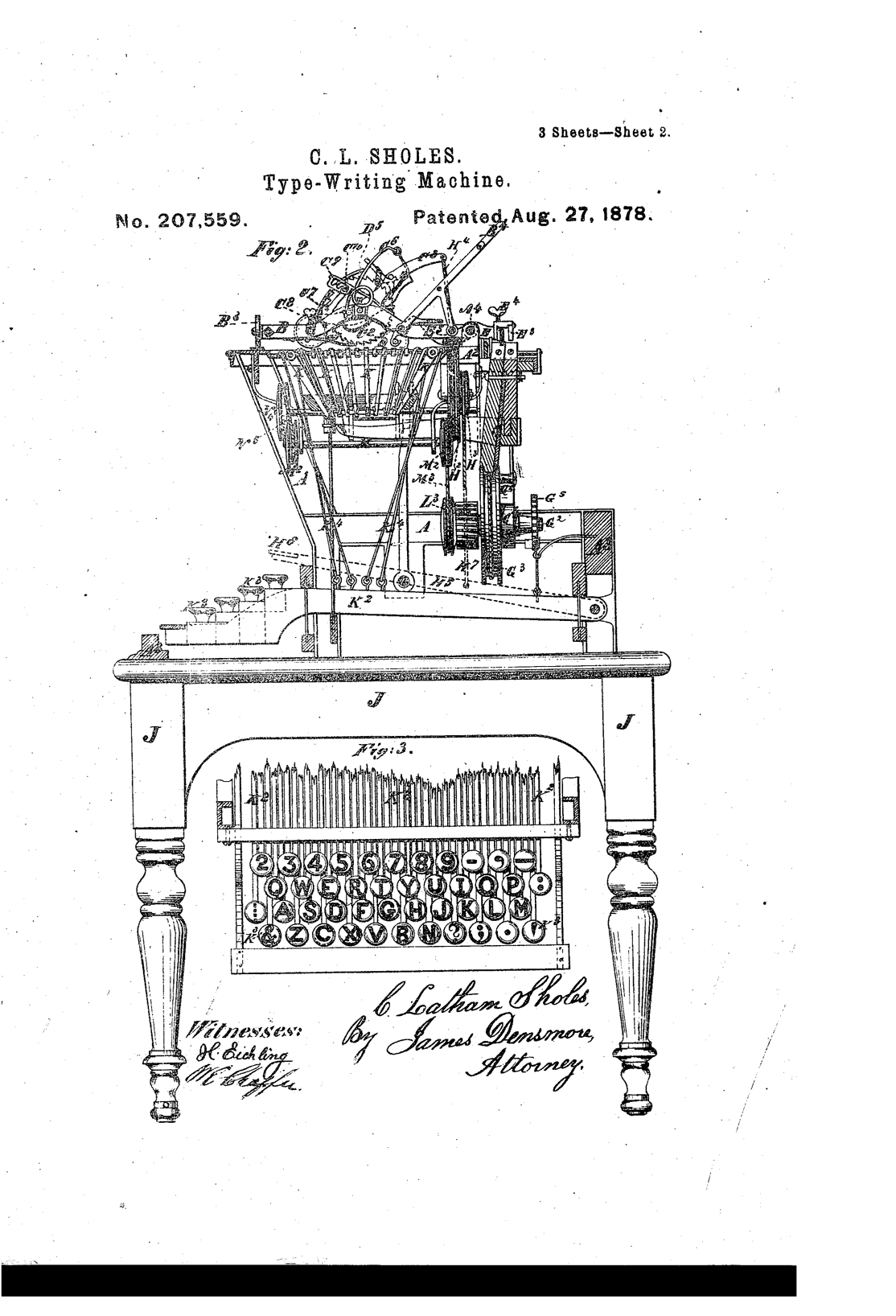

Remington makes further modifications and releases the first model of the Sholes and Glidden typewriter with the following layout (patented by Sholes)14

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 -

Q W E R T Y U I O P

A S D F G H J K L M

Z C X V B N ? ; . !

Layout hypotheses15

A on the home row because of its relative frequency

S out of place and closer in proximity to E and Z to aid Morse code receivers, as the codings for Z and SE are equivalent in American Morse code

- Z (··· ·)

- SE (… .)

Q moved to the edge because of its infrequent usage

T moved to the central region of the board because of its frequent occurrence

- also in closer proximity to H due to the high frequency of the bigram TH

O positioned close to 9 as it was also used to represent the numeral zero

R out of alphabetical order and adjacent to E because ER is one of the most frequent bigrams in the english language, second only to TH16

C out of place and in close proximity to S because their American Morse code representations resemble each other (see above figure)

it is also apocryphally theorized that the QWERTY layout was influenced by bigram frequency analysis to mitigate the risk of type-bar jamming, although this has not been thoroughly substantiated with much evidence

Modern QWERTY

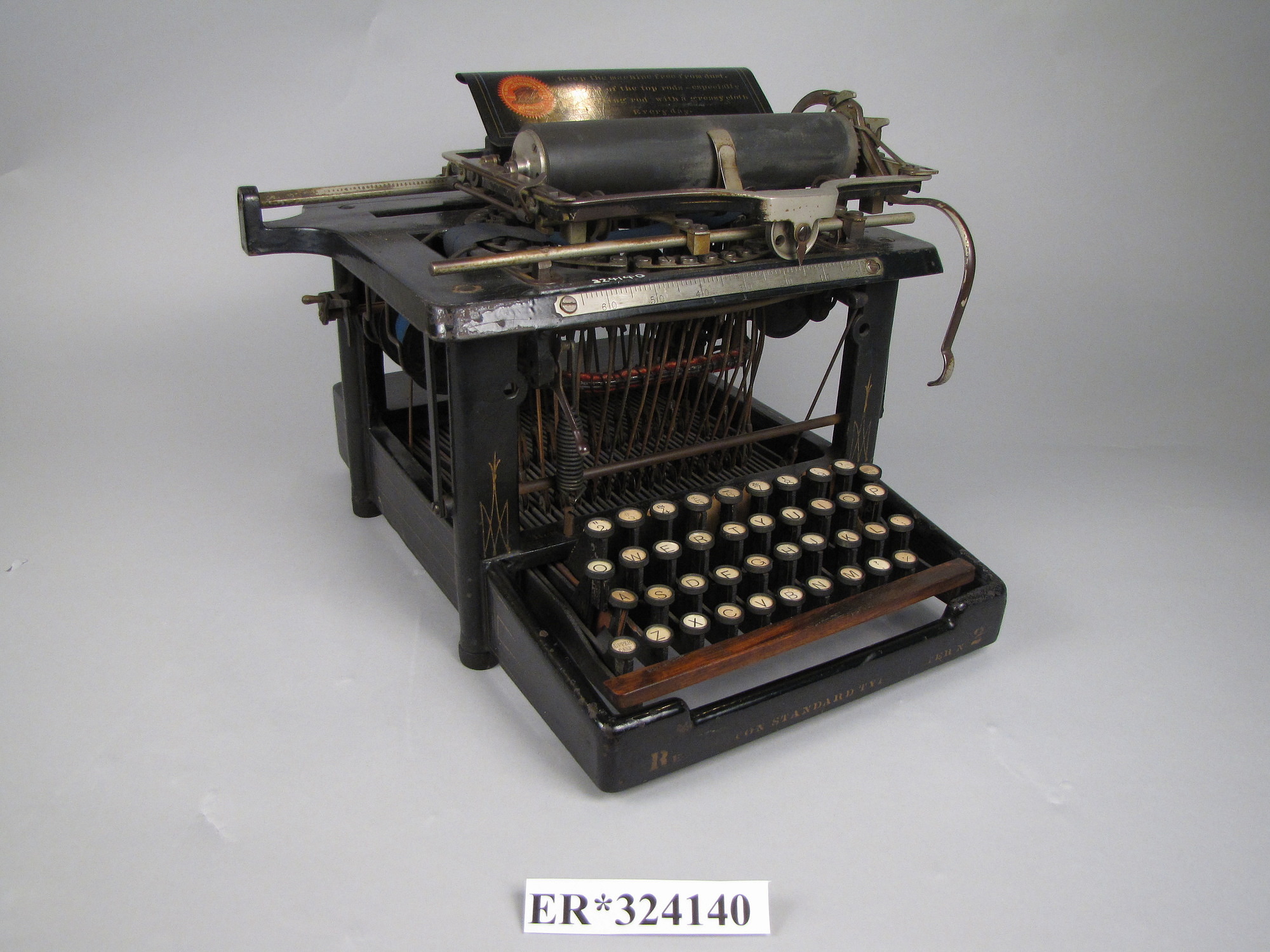

in 1882 Remington makes a minor modification to the 1878 Remington Type-Writer No. 2 layout to avoid copyright infringement

the positions of the C and X keys are swapped, and the M key is positioned on the bottom row

this is released as the Remington Standard Type-Writer No. 2 with the QWERTY layout as we know it today

- note the minor layout changes mentioned above

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 -

Q W E R T Y U I O P

A S D F G H J K L ;

Z X C V B N M ? .Alternative keyboard layouts

From the above history, you might be wondering, what does this have to do with typing ergonomics? Well, to put it into a historical perspective, there are several factors that influenced the layout as mentioned above:

baseline alphabetized ordering (with existing vestiges today in D, F, G, H, J, K, L)

affiliation with Morse code

nascent introduction of touch typing17, as compared with hunt-and-peck or two-fingered typing

If we consider the overall shape and form of typewriters versus modern keyboards, there are some notable statistics to keep in mind, especially when considering the increased speed with which we type today given modern key switch technologies.

In a famous paper from 1982, The QWERTY keyboard: a review18, it is noted, for example, that in QWERTY on average only 32% of time is spent on the home row, 52% on the back row, and 16% on the front row. This leads to excessive row hopping for frequently-used sequences, requiring reaches from the home row for 68% of all typing. This skewness towards the back row explains why sculpted ergonomic keyboards are typically curved upwards (to facilitate the above average time spent on the back row, away from the home row where the fingers would otherwise be naturally rested).

We could argue from this alone that the keyboard layout envisioned jointly by Schwalbach, Sholes, Densmore, and Remington was not designed for modern keyboards.

In 1936, August Dvorak, an educational psychologist and professor of education at the University of Washington in Seattle, patented an alternative keyboard layout (referred to as the Dvorak layout) where 70% of letter keyboard strokes are done on the home row and only 22% and 8% on the top and bottom rows respectively.

In 2006, Shai Coleman, a rather reclusive figure, invented an alternative to both the QWERTY and Dvorak layouts, called the Colemak layout19. It is supposed to be easier to learn than Dvorak, as it shares more keys with QWERTY, while retaining the property of, on average, having 74% of typing done on the home row.20

This is ultimately the keyboard layout I decided on, and it was a lifesaver for my wrists and hands.

Mastering Colemak

At this point, I had decided to make a transition to Colemak. Thankfully, there was a collection of learning resources21 on the site. I mainly used the Keyzen-Colemak22 tool. I picked a 1-2 week period when I knew I was going to have some time off, and a dramatic reduction in my typing speed and proficiency would have minimal impact on my work.

After committing to learning the layout for 1-2 weeks, I almost immediately started to experience relief in my hands and fingers. After about 2-3 years I eventually further transitioned to the Colemak Mod-DH23 setup, which makes a few minor modifications to put even less strain on the index finger.

As a Mac user, my setup is mainly comprised of the Karabiner Colemak configuration24.

Conclusion

For 5 years I have experienced no strain or pain in my hands as a result of the keyboard layout transition. Typing has in fact become a kind of delight, since the sensation of typing with the Colemak layout is akin to playing the piano, perhaps ironically harking back to the original “literary piano” layout of the 1868 Sholes patent. It was honestly a lesson for me to not take any conventions for granted, especially when those conventions have a negative impact on your quality of life.